The Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) fossils on display here at UC Merced possibly began their lives as far back as approximately 120,000 years ago. Unfortunately, more exact dating wasn't possible due to the lack of intact organic material in the fossils. Despite this, there is still a wealth of information available that can help us better understand how Columbian mammoths lived in this area, and, more specifically, how those on display here may have met their end.

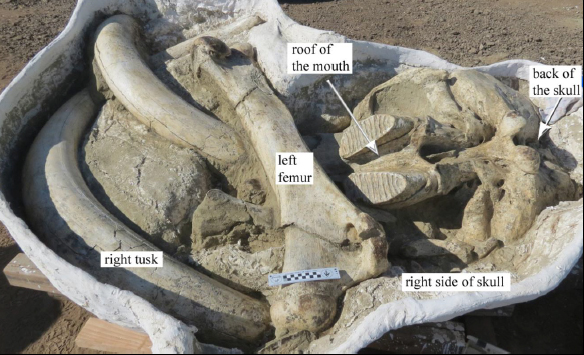

There are two Columbian mammoth fossils on display. The fossil on the left is a juvenile skull with an attached tusk. The larger specimens on the right are an adult skull, a femur, and a tusk:

While it wasn't possible to determine when these specimens lived, it was possible to estimate the age of the adult. By examining the bones, one could make an approximate estimation of an animal's age when they died.

The first strategy that paleontologists used to determine the age of the adult was to look at the femur. Both ends of the adult mammoth's femur were completely fused--this fusion occurs when bone growth ceases. Given this, the paleontologists were able to estimate that the mammoth was older than 30 years of age, which is the age at which Columbian mammoths tended to stop growing.

The second strategy was to look at the mammoth's teeth. Columbian mammoths had four functional molars at any given time during their lives. These molars were replaced five times over the mammoth's lifespan. Beginning in infancy, the first molars were similar in size to an adult human molar. These were gradually replaced by larger molars as the mammoth aged, with the largest reaching upwards of 1 foot long. In addition, as each molar was replaced, the ridges in the tooth became more numerous and more pronounced. This mammoth had a second molar present, meaning that the final molar had not yet erupted. Given this, as well as by taking note of the wear on the teeth, the paleontologists estimated the adult mammoth's age at approximately 49 years old.

The final hours of these mammoths' lives were most likely not very pleasant. There is evidence to suggest that there was a wildfire present at the site. In all likelihood, these mammoths died in a stream bed while the fire raged around them. After the fire other animals drifted with the stream and settled with the mammoth remains.

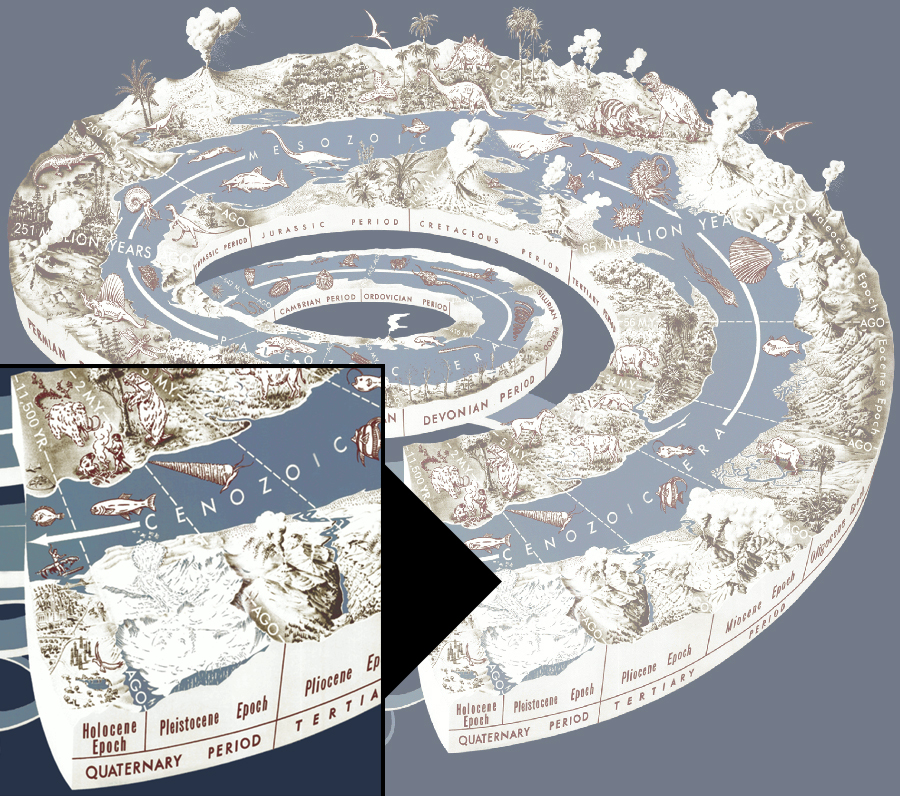

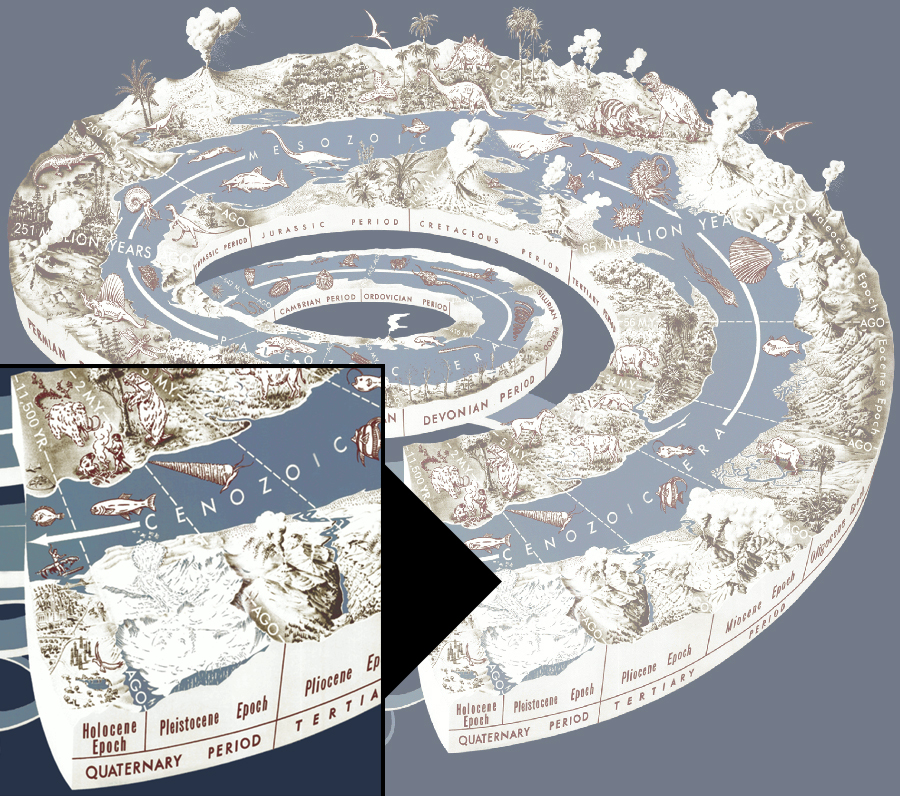

The Pleistocene epoch, or what we've popularly come to refer to as the "Ice Age," was a period from approximately 2 million to 12,000 years ago. The climate during the Pleistocene was marked by a repeated expansion and retraction of glaciers in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. In North America, glaciers extended as far down as what is currently New York City.

Source: Smithsonian.com

Source: Smithsonian.com

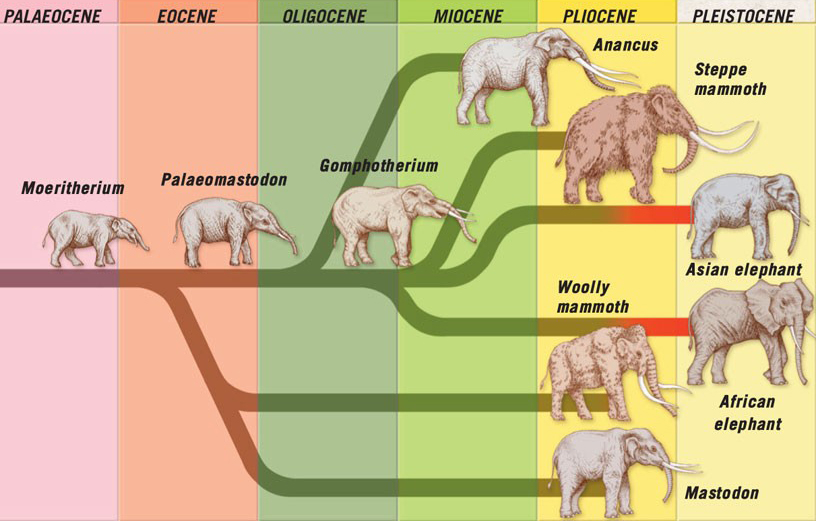

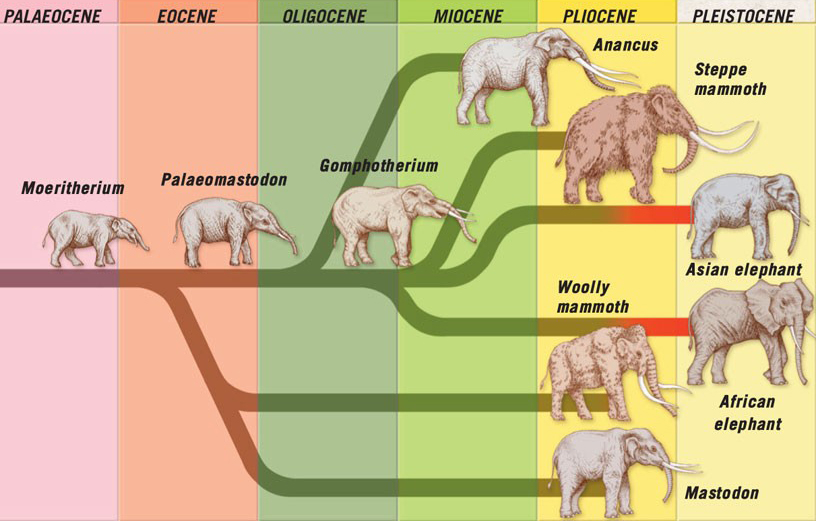

The first mammoths that inhabited North America were the steepe mammoths, which migrated across Beringia (or, the Bering Strait) from East Asia. During periods of maximum glacial coverage, mammalian megafauna (or large animals) often migrated back and forth across Beringia. This land bridge was made possible due to the retracted sea levels caused by glaciation. The Columbian mammoths that descended from the steppe mammoths lived across North America and remains have been discovered as far south as Costa Rica.

Source: q-files.com

Source: q-files.com

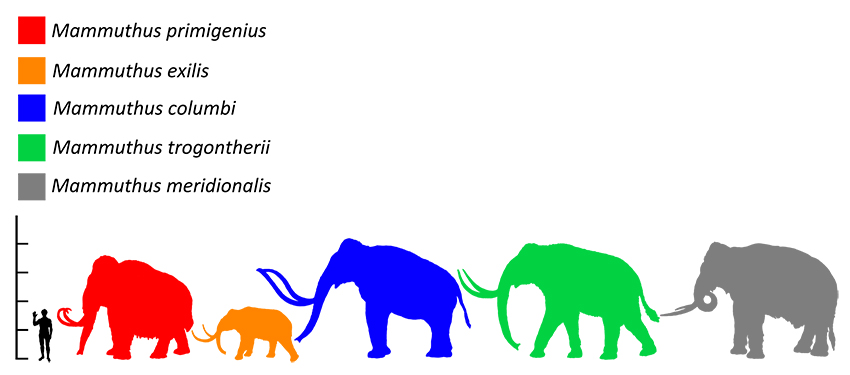

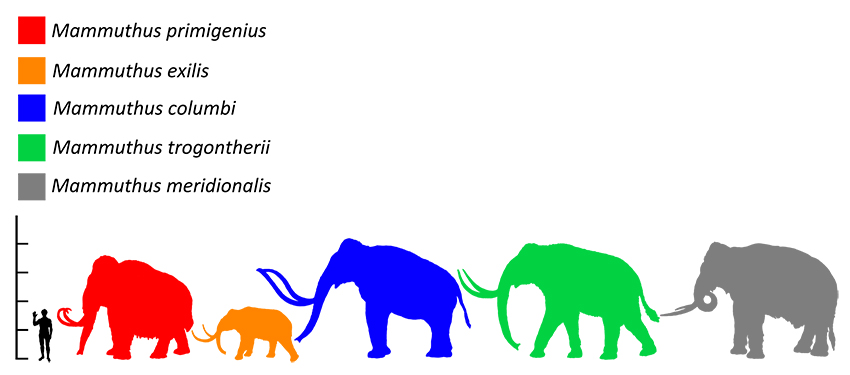

Columbian mammoths typically grew to be about 14 feet tall at the shoulder, and weighed an average of 10 tons. They were typically the same size as their forbearers the steepe mammoth, but were larger than the wooly mammoth or the modern African elephant. The mammoths listed below are, from left to right: the woolly mammoth, the pygmy mammoth, the Columbian mammoth, the steepe mammoth, the southern mammoth.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

Interestingly, the pygmy mammoth lived exclusively on the Channel Islands off the coast of present-day Los Angeles. These mammoths, which descended from the Columbian, likely swam to the island, and as time went on their body sized adapted to their more confined surroundings.

Columbian mammoths lived in communities much like modern elephants. They were very social, and lived in matriarchal (female-led) herds. Mammoths, like elephants, were herbivores, and their diet consisted of grass, brush, and other vegetation. They would use their trunks to gather food, and would also use their tusks to dig up larger plants and scrape the bark from trees.

Columbian mammoths had a quite long lifespan, and could live up to 80 years of age. A common cause of death among mammoths was prompted by the loss of their last set of molars. When this happened, they could no longer eat, and would subsequently die of starvation. As adults, mammoths typically did not have many predators, but juveniles would often fall prey to such animals as the dire wolf, the saber-toothed cat, and the American lion. Male mammoths, given the frequency spent away from herds, may also have been more prone to natural hazards such as sinkholes or tar-pits, such as the ones found at La Brea in Los Angeles, CA.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

As part of The Arboleda Drive Freeway Project on Highway 99, just south of Merced, paleontologists monitored excavation zones as required by the project's Environmental Impact Report. On the project's second day of activity, excavation was halted due to the discovery of fossil remains. Over a period of a few months, the paleontologists recovered a wide range of fossils from a variety of different organisms dating from the middle and late Pleistocene to the early Holocene.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

During the recovery process, a total of 1,667 fossils were identified and collected. The range of organisms represented by the findings were incredibly rich, and the large mammals identified included:

- Columbian mammoth

- giant ground sloth

- dire wolf

- western camel

- American llama

- ancient bison

- horses of at least two types

- deer

Smaller animals unearthed included:

- jackrabbit

- ground squirrel

- kangaroo rat

- vole

- deer mouse

Some of the remains of these other animals are also on display in this exhibit.

As noted by the paleontologists in their report, "Fossils from the area are poorly known and fossils recovered from this project will be an important contribution," and that a goal "will be to interpret the relationships of any recovered fossils to known fossil taxa and assemblages in the region." These fossils will certainly provide a wealth of information to researchers looking to understand the history of the Central Valley.

The pictures below detail the steps taken by the excavation crew to unearth and stabilize the mammoth fossils that are on display.

>

Photos courtesy of CalTrans

Photos courtesy of CalTrans

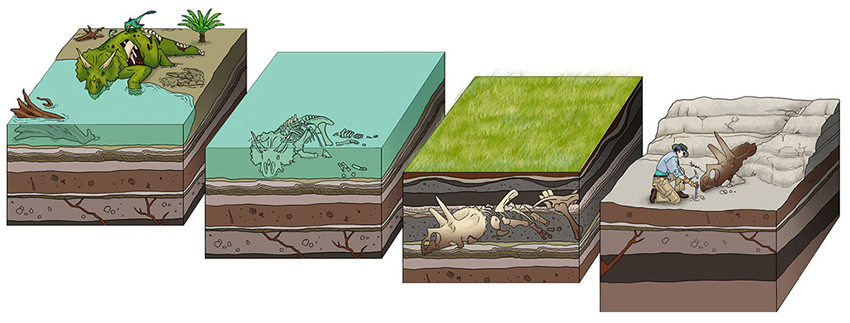

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

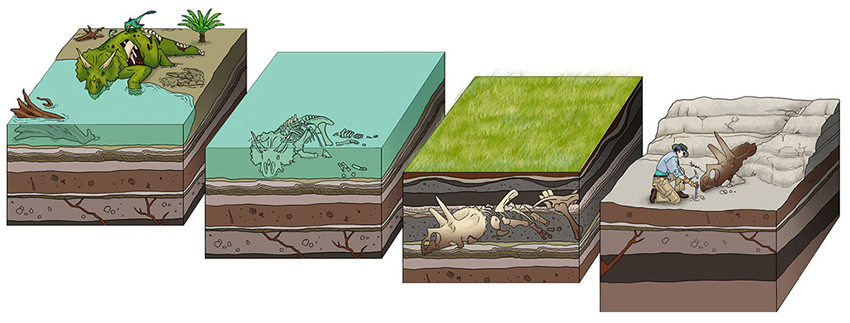

When we use the term "fossils," what we are talking about are any remains that exist of past life. These remains can take numerous different forms, including:

Molds -- Where the original organism has completely dissolved, leaving only an imprint in a rock or other surface. The below molds are from Cambrian era trilobites that lived over 541 million years ago.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

Fossils that have undergone Perimineralization -- This process happens when an organism is buried, and when the empty or open spaces of an organism (spaces which were filled with gas or liquids during the organism's life) are then filled with groundwater. The minerals from the groundwater then occupy all the vacant spaces within an organism, and have the potential to produce very detailed fossils. For this process to produce the greatest detail, the organism must be buried relatively soon after death. For example, the following piece of wood that has become mineralized with quartz. This kind of wood is more commonly called "petrified" wood.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

Replacement -- This is the process through which an organism's bone or tissue is completely replaced with another mineral. So, for example, a sea shell's compounds could potentially be replaced entirely with silica. The shell's below have had their organic matter completely replaced with silica.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

The above processes can take millions of years to complete. But, in addition to the above, we also have access to the actual skeletal remains of a wide variety of organisms.

Source: ndstudies.gov

Source: ndstudies.gov

Being in possession of skeletal remains provide paleontologists with a wider wealth of information about an organism. Sometimes, it is even possible, given the right burial environment, for soft organic material (such as hair, skin, and cartilage) to be present.

If one has access to soft organic content, it could be possible to extract genetic information from that organism. These kinds of discoveries allow for research that explores the possibility of de-extinction.

Ecology of the Middle Pleistocene in Central California

The ecological makeup of California during the Pleistocene can best be described as resembling the Serengeti ecosystem in Tanzania, Africa, though it has been said that the ecological diversity of the Californian Pleistocene dwarfs that of the Serengeti. The landscape was filled with large swaths of wild grasslands, and the climate for which the area is now known was beginning to be established. The presence of megafauna, such as the Columbian mammoth, contributed in large part to the shaping and evolution of the ecosystem. Mammoths, as part of their feeding habits, helped reduce the amount of trees and large shrubs present, thus assisting in the development of large grassy areas perfectly suited to grazing megafauna such as the giant ground sloth (a ground sloth the size of a modern elephant), the western horse, the western camel, bison, pronghorn, and the Columbian mammoths themselves.

These grazing megafauna were accompanied by an equally diverse range of predatory species. Predatory megafauna such as saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, American lions, American cheetahs, and the short-faced bear (one of the largest terrestrial mammalian predators ever to have lived) roamed the grasslands and preyed on their herbivore counterparts.

Source: Wikipedia.com

Source: Wikipedia.com

As the Pleistocene epoch transitioned to the Holocene epoch, a mass extinction event occurred. Almost the entirety of the North American megafauna vanished. There are many theories as to why this mass extinction took place. Some argue that the environmental changes that occurred at the end of the last glacial period had a negative effect on the overall livable habitat for these creatures. Others argue that they died as a result of overkill by humans, who had made their entry into North America towards the end of the Pleistocene epoch.

Yeakel Ecological Dynamics Lab

Principal Investigator: Justin Yeakel

The Yeakel Ecological Dynamics Lab focuses on the constraints that shape diet and it’s impact, and how changes can affect community dynamics over both ecological and evolutionary time. The Yeakel Ecological Dynamics Lab use both theoretical and empirical approaches to address many different aspects of problems that fall within the study of ecological systems. The Lab tests how diet affects population dynamics and interactions on a vast time scale. Studying diet can help discover how organisms choose their food source depending on the environment, how diet based behaviors affect ecological communities as a whole, and identify the evolutionary consequences for these dynamics. Among various projects underway, the Lab is analyzing traits of Pleistocene animals found in the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, CA.

For more information, visit http://jdyeakel.github.io/.

For more information, visit http://jdyeakel.github.io/.

Blois Paleoecology Lab

Quaternary Ecology, Biogeography, and Phylogeography

Principal Investigator: Jessica Blois

The Blois Paleoecology Lab investigates the relationship between species, communities, and the environment, focusing on the past 21 thousand years of life on earth in order to inform the next one hundred years and beyond. The Blois Paleoecology Lab has numerous diverse projects, generally united by a focus on spatio-temporal processes underlying the structure of biodiversity and a strong “Conservation Paleobiology” focus, trying to understand how we can use the fossil record to inform conservation decisions for the future. Major themes of the Blois Paleoecology Lab include community dynamics, paleo-modeling, space/time genomics, traits, and California natural history.

For more information, visit https://jessicablois.com/.

For more information, visit https://jessicablois.com/.

Numerous organizations and individuals were involved in making this exhibit possible:

Mark Aldenderfer, as former Dean of UC Merced's School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts provided invaluable financial and informational support for this project. This exhibit would not be possible without Professor Aldenderfer's work in bringing these fossils to UC Merced.

Jake Biewer and Professor Julia Sankey from CSU Stanislaus provided much needed consultation support, and assisted with the stabilization of the fossils.

Central Region Hazardous Waste and Paleontology Branch, California Department of Transportation was present at the original dig site, and provided essential transportation and logistical support for the fossils.

Cogstone Resource Management was present at the original dig site, and provided the necessary paleontogical monitoring of the dig site. Paleontologists from Cogstone prepared the Paleontogical Monitoring Report required for the dig site, and were crucial in the proper excavation and stabilization of the fossils.

The Fossill Discovery Center of Madera County were very helpful with providing information used in preparing this exhibit.

Justin McConnell, Joseph Ramos, and Bryan Spielman from UC Merced Facilities Management provided invaluable logistical and materials support for this exhibit, and were responsible for the fabrication of the mammoth exhibit enclosure.